Recently I had the pleasure of making a presentation at the Ōpōtiki Library Pecha Kucha event, which turned out to be a fascinating evening of very interesting speakers covering a wide and diverse range of subject matter. If you are not familiar with the format, a speaker presents 20 slides, and has 20 seconds exactly to talk about each slide. The name means is a transliteration of a Japanese phrase that means "chit chat" and it was in Tokyo in 2003 that the first event was hosted. Since then this format has become very popular, in over 1000 cities, providing the ideal platform for people old and young to share stories, creative ideas, and projects.

This is the seventh night of Pecha Kucha for the Ōpōtiki Library, and each night has sold out its allocated 100 seats, proving what a popular event this is, drawing on the creativity and ideas of our wonderfully diverse community. In addition, these events have raised almost $15,000 towards fundraising for Te Tahuhu o Te Rangi, the proposed new technology and research centre for Ōpōtiki. Putting my presentation together provided an opportunity to reflect on my journey and some of the interests and ideas I like to explore in this blog, and in occasional pieces for the Eastern Bay Life So if you could not make it to Ōpōtiki, or missed out on a ticket, I would like to share my 20 images and 20 seconds of story with you, as presented on the night. However, here I invite you to explore deeper through the links I have added here.

Pecha Kucha at Ōpōtiki Library 02.08.18

|

| 3.This spectacular view became a familiar sight to me almost every day. Te Pane o Mataoho, or Māngere Mountain is one of the largest and most intact volcanic cones in Auckland, and hundreds of years ago was the centre of a complex of pā sites, gardening areas, and villages, described by some as a centre of pre-European urbanization. |

|

| 7. Researching the geology and history of Auckland, I was shocked to discover the history of degradation and destruction of its volcanic features by quarrying, urban encroachment, or simply because maunga were considered inconvenient. Nowhere was this more evident than on a South Auckland peninsula called Ihumātao. |

|

| 8. In time I became involved with the Save Our Unique Landscapes fighting a housing development adjacent to the Otuataua Stonefields Historic Reserve at Ihumātao. The site of the earliest settlement in Tāmaki Makaurau, and here one finds the human, geological, and environmental history written in the landscsape. |

|

| 13. Viewing the landscape in the context of the geological timescale, we can see that nothing stands still. Erosion and deposition are continuous cyclic processes. Sediments become buried and turn to rock, rocks are uplifted and eroded. Mountains become deformed, sheared and brittle, and earthquakes rock and reshape our landscapes. |

|

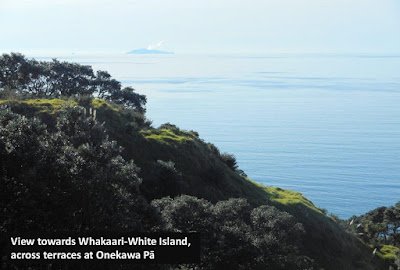

14.

Volcanism, a force feared by humans since recorded history

is a neccesary force in creating new land, and forming our

mineral rich and fertile volcanic soils. From Ōpōtiki we see White Island, where the Taupō Volcanic Zone extends to the

world's longest chain of active submarine volcanoes and hydrothermal vents,

stretching to Tonga.

|

|

| 15. Closer to Ōpōtiki and on land, the Taupō Volcanic Field sits atop a rift in the crust spreading at around 9mm per. year. In this area the crust is only 16km thick, half the usual 30km thick, and there is evidence of a magma body 50 by 160 kilometres just 10 kilometres below the surface. |

|

| Other clues in today's landscape tell of constant change and catastrophic events. Gravels deposited during an ice-age six hundred thousand years ago are seen in coastal cliffs at Waiotahi. Above these sit ash deposits from the Taupō Volcanic Zone, first erupting some three hundred thousand years ago. |

|

| 18. New Zealand is a country on the rise, the whenua we call home a small portion of the mostly submerged continent of Zealandia. The same processes that stretch and pull the crust of the Taupō Volcanic Zone, thrust, fold, and distort the rocks of the Ruakumara Ranges, while rainfall and earthquakes assist the erosion of these brittle slopes. |

|

| 20. I hope you have enjoyed this journey with me through our dynamic whenua. I invite you to explore further through my blog Aotearoa Rocks, my facebook page Māngere Bridge Rocks, and to check out the developing geological display at the Ōpōtiki Museum. And of course, thank you to the Ōpōtiki Library for organizing this great event. |

Rocking the Ōpōtiki Museum!

Over the past year I have had the pleasure of working on refreshing the geological display at Ōpōtiki Museum, adding new material and providing interpretation. I would like to share some brief glimpses of the display, and encourage you to check out the full display at the museum, along with a wealth of other historical material from the Eastern Bay of Plenty. open Monday to Friday 10am till 4pm, and Saturday 10am till 2pm, at 123 Church Street, Ōpōtiki.

|

| Above and below. Distinctive yellow sulphur crystals from Whakaari/White Island. Sulphur mining took place on the island till the late 1930's. |

|

| Detail of pumice, showing gas bubbles preserved in volcanic glass. Pumice can be up to 90% air, and can float in water. |

|

| Unusual grey coloured pumice/volcanic glass, washed up on Ōhope Beach, most likely from Whakaari/White Island. |

Unless otherwise credited, all images in pecha kucha and this post by author.

Thanks to the Eastern Bay Life Magazine, published by the Whakatāne Beacon, for publishing regular pieces on the natural history of the Bay of Plenty. Follow the links below

to view, reproduced with the permission of the Whakatane Beacon.

Fire, ice and dust. Ice Age in The Bay of Plenty.

Ice Age rocks Waiotahi

Waioeka, Waters of the weka

to view, reproduced with the permission of the Whakatane Beacon.

Fire, ice and dust. Ice Age in The Bay of Plenty.

Ice Age rocks Waiotahi

Waioeka, Waters of the weka