This post was originally published in September 2019. On 9th December 2019 the volcano explosively erupted while 47 people were on the Island. This blog post is dedicated to the memory of the 21 victims passed away as of 29 January 2020. I also acknowledge rescue and disaster recovery workers worldwide, and the work of volcanologists worldwide.

|

| Te

Puia o Whakaari/White Island, view from eastern Bay of Plenty looking into main crater with steam fumeroles visible just above sea-level. Source: Author (2017). |

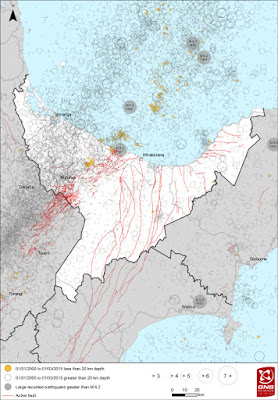

While conditions in the Whakatāne Harbour were relatively calm, the hour and a half boat trip thanks to White Island Tours saw some fairly green passengers by the end of the trip due to the rolling swell encountered as soon as the boat reached deeper water. Whakaari is in fact a large volcanic complex, approximately 16 x 18 km, the majority of which is underwater, with only the peak visible above water as the island we can see. The island volcano is part of a belt of volcanism that starts at Ohakune (part of a region commonly referred to as the Taupō Volcanic Zone (TVZ)) and continues offshore to Whakaari.

If you would like to know more about the Taupō Volcanic Zone, and the geological forces that have shaped the Eastern Bay follow this link to a previous post "Ōpōtiki, the shifting and fiery land around us. A thrilling story of volcanism and tectonics...."

It may surprise you that approximately 70% of the Earth’s volcanic activity occurs underwater, and Whakaari is part of a chain of underwater volcanoes extending as far as Tonga called the Kermadec Arc. A distant perspective may give us a sense of the island as relatively small, but it is a significant landmass approximately 2 x 3km. Setting foot on the island gives one an entirely new perspective of this surreal and raw landscape, constantly changing and subject to the influences of volcanic activity, landslides and earthquakes, and influences of hydrothermal gases and liquids.

The Māori name Te Puia o Whakaari means “The Dramatic Volcano” or “that which can be made visible” and is explained in two Māori legends. One tells of Maui fishing the North Island out of the ocean, accidentally stepping on the land and some of the fire burning on it. Where he shook this off his foot into the sea this became Whakaari. Another legend tells of the arrival of Chief Ngatoro-i-rangi bringing fire from Hawaiiki. Leaving his sisters at Whakaari, he voyaged to Maketu and onwards to Tongariro. Finding it so cold at Tongariro he called on his sisters to send fire. Volcanic and thermal activity between Whakaari and Tongariro marks the route of the underground journey taken by spirits bearing fire. The volcano, most of which is underwater with the main crater only 30m above sea-level, has been continually active since human settlement of New Zealand, with one of the most the most active periods between 1976-1982. Presently the volcano is at an alert level of 1, meaning minor volcanic unrest.

|

| Report on sequence of eruptions occurring between 1976 and 1982 when ash clouds several kilometres were formed and lava bombs up to a metre in diameter were ejected. Also significant changes to craters and vents took place. Source: GNS.cri.nz |

The name White Island was given by Captain Cook who only ever saw the island from a distance. The most commonly cited theory was it was referring to the ever-present white steam-plume. However, according to some researchers Cook noted the similarity of the rocks around the Island to the Needle Rocks, off the Isle of Wight, and marked our "White Island" on a chart prepared for Joseph Banks as "The Isle of Wight".

The island passed into the hands of European officers in the mid-19th century, allegedly for two hogsheads of rum. From 1885 onwards the island was the site of commercial sulfur mining, which continued till 1933 despite several miners being killed by a landslide from the crater wall in 1914. Understandably such a unique, dynamic, and relatively accessible volcanic feature has long been of interest, both for scientific interest and tourism , as can be seen in this photo of an early 20th century field trip to White Island.

The history of sulphur mining and the associated loss of life and injuries on the island are well documented, and I have added here some links that tell the grim story of the brutal conditions, efforts to make mining profitable, and the loss of lives.

The island passed into the hands of European officers in the mid-19th century, allegedly for two hogsheads of rum. From 1885 onwards the island was the site of commercial sulfur mining, which continued till 1933 despite several miners being killed by a landslide from the crater wall in 1914. Understandably such a unique, dynamic, and relatively accessible volcanic feature has long been of interest, both for scientific interest and tourism , as can be seen in this photo of an early 20th century field trip to White Island.

The history of sulphur mining and the associated loss of life and injuries on the island are well documented, and I have added here some links that tell the grim story of the brutal conditions, efforts to make mining profitable, and the loss of lives.

|

| New Zealand fur-seals lounge in the sun on the rocks around the island. The water's support rich web of fish, sea-birds, and marine mammals. Source: Author (2019). |

|

| Above and below. Silica-rich minerals are a common sight, precipitated from mineral-rich hydrothermal fluids and volcanic gases. Source: Author (2019). |

|

|

| Above and below. Crystalline sulphur precipitated from volcanic gas fumeroles form distinctive, surreal, and beautiful "chimneys". Source: Author (2019). |

|

| A lava bomb deposited in ash shows signs of recent deposition, with a small impact depression around the lava still visible in the ash. Source: Author (2019). |

|

| A "breadcrust"lava bomb shows a distinctive crust, caused by very rapid cooling of lava as it travels through the cold air. Source: Author (2019). |

|

| Several cameras monitor activity in real time, and a 10 minute snapshot can be seen at the GeoNet website. Monitoring also includes seismometers (earthquake activity), UV spectrometers (SO2 emission rate), and GNSS (ground deformation). Visit the GeoNet monitoring website here. |

|

| As one leaves the island the remains of the sulphur works provide a stark reminder of the precariousness of human life and endeavours on an active volcano. Source: Author (2019). |